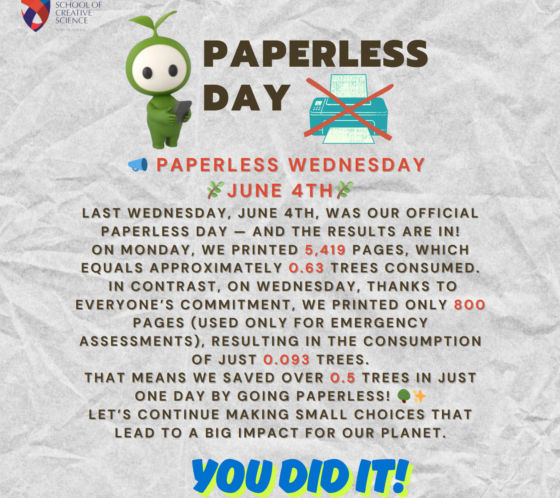

Jane Goodall Is Still Wild at Heart

Half a century ago, she journeyed into the Tanzanian jungle to change how the world saw chimpanzees. Today the world’s most famous conservationist is on a mission to save their lives.

By PAUL TULLIS MARCH 13, 2015

Jane Goodall was already on a London dock in March 1957 when she realized that her passport was missing. In just a few hours, she was due to depart on her first trip to Africa. A school friend had moved to a farm outside Nairobi and, knowing Goodall’s childhood dream was to live among the African wildlife, invited her to stay with the family for a while. Goodall, then 22, saved for two years to pay for her passage to Kenya: waitressing, doing secretarial work, temping at the post office in her hometown, Bournemouth, on England’s southern coast, during the holiday rush. She had spent her last few days in London saying goodbyes and picking up a few things for the trip at Peter Jones, the department store in Chelsea. Now all this was for naught, it seemed. The passport must have fallen out of her purse somewhere.

It’s hard not to wonder how subsequent events in her life — rather consequential as they have turned out to be to conservation, to science, to our sense of ourselves as a species — might have unfolded differently had someone not found her passport, along with an itinerary from Cook’s, the travel agency, folded inside, and delivered it to the Cook’s office. An agency representative, documents in hand, found her on the dock. “Incredible,” Goodall told me last month, recalling that day. “Amazing.”

Excited and apprehensive, she boarded the ship, the Kenya Castle, with her mother and uncle, and together they inspected the vessel, circling its decks, looking out the porthole in the room she would occupy for the better part of a month. Then her family departed, and at 4 in the afternoon, the ship cast off. Twenty-four hours later, as most of the passengers were suffering from seasickness on their traverse across the Bay of Biscay, Jane Goodall was at the prow of the ship — “as far forward as one could get,” she wrote to her family. Her letter also recorded, in a detailed manner that foreshadowed the keen observational skills she would bring to her research as well as the literary bent she would deploy in reaching a broad audience, how the sea changed color as the bow rose and fell with the waves. “The sea is dark inky blue, then it rises up a clear transparent blue green, and then it breaks in white and sky blue foam. But best of all, some of this foam is forced back under the wave from which it broke, and this spreads out under the surface like the palest blue milk, all soft and hazy at the edge.”

‘Aloneness was a way of life,’ Goodall wrote of her time in the jungle 50 years ago. Today, as a globe-trotting conservationist, she can neither avoid nor refuse human contact.

Because the Suez Canal was closed — war broke out on the Sinai Peninsula several months earlier — the ship took the long route, around the Cape of Good Hope. Three weeks passed before the Kenya Castle reached Mombasa, on the Indian Ocean. Goodall was sad to leave her cabinmates and the other friends she made on the journey: an engineer, a governess, a man volunteering at a leper colony. But she had waited a long time for this moment. She was just 8 when, inspired by the stories of Tarzan and Dr. Doolittle, she resolved to live in Africa one day.

Within two months of her arrival, Goodall met the paleontologist Louis Leakey — Nairobi was a small town for its white population in those days — and he immediately offered her a job at the natural-history museum where he was curator. He spent much of the next three years testing her capacity for patient, repetitive work, in particular during a summer expedition of several weeks to Olduvai Gorge, where Leakey’s wife, Mary, also a paleontologist, would later find the hominid fossils that proved the African origins of homo sapiens. Goodall’s job was to rise at dawn and spend hours on her hands and knees, clearing away dirt and rock with a pick, in July and August, two degrees south of the Equator. Evenings meant hours listening to Leakey’s theories about physical anthropology and his ideas of how they might be proved.

He happened to believe in a hypothesis first put forth by Charles Darwin — and by 1957, largely forgotten — that humans and chimpanzees share an evolutionary ancestor. Close study of chimpanzees in the wild, he thought, might tell us something about that common progenitor. He was, in other words, looking for someone to live among Africa’s wild animals. One night at Olduvai, he told Goodall that he knew just the place where she could do it: Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve, in the British colony of Tanganyika (now Tanzania). A forbidding environment, no humans lived there, though it was thought by many locals to be where they would be reborn, after death, as chimpanzees.

In July 1960, Goodall boarded a boat, far smaller than the Kenya Castle, and after a few hours motoring over the warm, deep waters of Lake Tanganyika, she stepped onto the pebbly beach at Gombe.

Last summer, almost exactly 54 years later, Jane Goodall was standing on the same beach. The vast lake was still warm, the beach beneath her clear plastic sandals still pebbly. But nearly everything else in sight was different. The jungle had reclaimed the clearing where she pitched her first tent. A ranger station and a small lodge stood nearby. Just out of sight, carved into the vegetation, were more cinder-block buildings that housed staff, researchers and their labs. Jutting into the lake was now a dock, where a boat was pulling up with a load of day-trippers from Kigoma, a small city to the south. All of this bustle was, of course, a result of the work Goodall began that day in 1960, which continues as one of the longest and most rigorously conducted inquiries into animal behavior.

For a good while in the beginning, Goodall had little human company. “Aloneness was a way of life,” she would write. Today, as a globe-trotting conservationist, Goodall can neither avoid nor refuse human contact. She radiates approachability; she typically dresses in khakis and an untucked oxford shirt. She can’t spend two minutes in a hotel lobby in Bujumbura or in an airplane seat waiting to depart for London without someone angling up to say how amazing she is. She can find relief from the crush of humanity only in hotel suites, in her childhood home of Bournemouth and here, on a remote shore of Lake Tanganyika, at the edge of a jungle few humans would set foot in had she not begun exploring it half a century ago.

An old friend and colleague of hers told me that Goodall, who turns 81 next month, regards Gombe as her “church” and her “refuge.” On this trip, though, a sense of sanctuary seemed out of reach — perhaps because she couldn’t resist the impulse to try to recruit new partners to her cause. I had accompanied her over Lake Tanganyika a couple of days earlier, and this morning we planned to take a walk in the woods and look for some chimps. But the trailhead of the path she wanted to take was blocked by a phalanx of tourists from the boat, and Goodall knew they would detain her if she tried to go that way.

Anthony Collins, a Scot who directs baboon research at Gombe and sometimes oversees its additional mission as an ecotourist destination, stood with us. He asked Goodall, “Where do you want to go?”

Chimps outside Goodall’s home in Gombe Stream National Park. (She was away.) Credit Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum, for The New York Times

“Away from all these people,” she said.

Just then Goodall saw Daniela de Donno Mannini, the head of the Italy branch of Jane Goodall Institute, the conservation NGO she founded in the 1970s. “Oh, look, it’s Daniela,” Goodall said enthusiastically. De Donno Mannini was in the area to visit an orphanage in Kigoma. She noticed Goodall at the same moment and came over, all smiles and hugs, a couple of her associates in tow. One of them took video of de Donno Mannini and Goodall chatting, then everyone posed for pictures with the great scientist. After a few minutes, the Italians went off with their park guide and the other tourists, heading into the forest to find chimpanzees.

“Let’s wait for them to get ahead,” Goodall said with resignation. “That’s the path I’d like to go up.”

Within 60 seconds, someone else appeared seeking an audience with Goodall: a Tory Parliamentary candidate and arts curator from Britain named Theodora Clarke. She was on her way to Burundi, she said, where she would help run a business-training program for local entrepreneurs organized by the Conservative Party. She asked for a picture. Goodall told her about a new office opening in Burundi, and she wanted to connect Clarke with someone from Roots & Shoots, an international youth group affiliated with her institute.

It would be great, Goodall suggested, flatteringly, “if you can get the U.K. government to support Roots & Shoots in Burundi” — as if Clarke had already offered as much, even if that was hardly the case.

“Well, I can’t make any promises, but I can certainly give you a few ears to tweak,” Clarke replied.

Goodall passed along a Roots & Shoots phone number. Soon Clarke walked off.

“Now who else is going to appear?” Goodall said. “Although, Tony,” she added, perking up, “this could be a very good contact.”

A cafe overlooking Kibira National Park, outside Bujumbura, Burundi. Goodall is working to help locals become tour guides, so they can earn income and have a stake in conservation efforts.

Credit Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum, for The New York Times

Another boatload of visitors was arriving at the dock. Before they could make their approach, Goodall headed into the woods.

“You can see why Gombe isn’t the same for me anymore,” she said. “It’s the same as everywhere else for me now.”

Gombe’s terrain is extremely rugged. The vegetation is tangled and thick; steep ridges rise abruptly from the lake, as much as 2,500 feet in just a mile and a half. The park cannot be reached by road, and its borders are a long walk from any village. These features make the preserve an Eden for chimpanzees, while mostly keeping people at bay. But Goodall had chosen — for my sake, perhaps, because as recently as two years ago she was still clambering over steep soggy slopes, pulling herself up with a vine — an easy path. Twenty minutes later, we reached a stream, and an odd moment ensued: Should I help her with her footing? An octogenarian in my company was walking on slippery rocks, wearing sandals no less. I crossed ahead of her and stood on the other side, waiting for her to hold a hand out; she did not.

We climbed a short way to a natural terrace in the hillside, where forest was overtaking a dilapidated cabin. This was Lawick Lodge, the one-room home she shared in the mid-1960s with Hugo van Lawick, the Dutch photographer dispatched by National Geographic to Gombe once Goodall’s astonishing findings were coming to light. I asked if she could still see, in her mind’s eye, the chimps with whom she once shared the forest.

“Yes,” she said with some sadness. “Mostly David Graybeard.” This was the first chimp to accept Goodall; as alpha male, his acceptance led others to follow suit.

The walk seemed to cheer Goodall. Even in July, the dry season, Gombe is a dense, deeply green forest, rich with life. Goodall knows its every sound — the call of every bird and whether a distant rustle of leaves is a chimp above, a baboon below or just the wind — and she enjoyed telling me stories about animals and men and what fools the former can make of the latter. Several times in this forest she has seen a bird, “the color of an English fox,” that no one else has identified, as far as she knows. And she laughed at the recollection of a Cambridge zoologist who was so proud of the sample of chimp scat he had collected at Gombe during a brief visit years before she got there — which was in fact from a bush pig. “I didn’t tell him,” she said. “What was the point?”

We didn’t encounter any chimps on our walk. Researchers and field staff who follow the animals daily, recording their behavior as Goodall began doing half a century earlier, could have directed us to them, as they do tourists. But, Goodall said, “I just don’t enjoy seeing the chimps when there’s loads of people around.” She didn’t see a single one during her four days at Gombe.

A little more than three months after arriving at Gombe the first time, Goodall was walking along a ridge when she came within sight of a termite mound. From 100 yards away, it took her a moment to realize that the black shape in front of it was a chimpanzee. She dropped to the ground, crawled on elbows and knees to within 50 yards and watched the animal climb on top of the mound with a long piece of grass. It sat there for the next several minutes, doing something with its hands, but Goodall couldn’t tell what, because her view was obscured by its back. She didn’t dare try to get closer; it would be a while yet before the chimpanzees became used to her presence. When it climbed down, the chimp she would name David Graybeard strolled to within 10 yards of Goodall before noticing her and stopping short. She noted an expression she could call only “shock” on his face. Then he turned and fled.

Inside Goodall’s home in Gombe Stream National Park. Credit Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum, for The New York Times

Two days later, Goodall returned to the same spot and saw David Graybeard again, this time with another chimp. Now she could see what David Graybeard was doing. Her finding, published in Nature in 1964, that chimpanzees use tools — extracting insects from a termite mound with leaves of grass — drastically and forever altered humanity’s understanding of itself; man was no longer the natural world’s only user of tools. More discoveries would follow. Chimpanzees hunt and eat meat. They plan violent attacks within their own groups. They lead complex social lives, suggesting an emotional capacity previously ascribed only to humans. Beginning when she was 26, without a college degree to her name, Goodall was doing groundbreaking work on issues that primatologists and anthropologists still grapple with today, anticipating entire avenues of research and hazarding explanations for behaviors that still aren’t fully understood 50 years later.

Not long after David Graybeard accepted Goodall’s presence, she was feeding the chimpanzees bananas and touching their infants. (Goodall would later need to curb some of these practices — providing bananas, for example, began to alter her subjects’ behavior, corrupting her data.) By that time, Leakey had garnered support from the National Geographic Society for continuing excavations at Olduvai, and he told its board about the young woman he sponsored who had made friends with free-living apes. Goodall’s first book, “My Friends, the Wild Chimpanzees,” was published by National Geographic in the mid-’60s, making her a star among the public, though it was regarded dimly by academia. Goodall recalled for me an episode at Cambridge, after the school made the exceptional decision, on the recommendation of Leakey, to admit Goodall into a Ph.D. program despite her lacking an undergraduate degree. When her book appeared — before her Ph.D. was even completed — her Cambridge mentor sputtered with rage: “It’s — it’s — it’s for the general public!” She told me she was nearly expelled from the program. That Goodall was a woman and attractive made her an easy object of the ethologists’ derision. How could she give the subjects of her research names? Think they had emotions? A social life? What was she doing out there?

Today the social lives of animals from whales to ants have been abundantly cataloged using Goodall’s methodology, which has helped to set the basic ground rules for contemporary field biology. Goodall herself became the first exemplar — before Carl Sagan, Stephen Hawking or Neil deGrasse Tyson — of the pop-culture scientist-communicator. She has inspired countless scientists, from the leader of Save the Elephants to the director of the Orangutan Project, at the same time as she has thrown open the door to other pioneering women in the sciences. And she did so by being as demanding as the Leakeys were of her, nightly grilling the graduate students who started coming to Gombe in the late 1960s.

Goodall married van Lawick in 1964, and they raised a son, known as Grub, at Gombe through his toddlerhood. With the formal training she acquired at Cambridge, as well as financial and logistical support from the National Geographic Society and Stanford University, Goodall built Gombe into a self-sustaining research station. After a raid in 1975 by rebels from Zaire, just across the lake, Goodall and the Americans stayed away during much of the next few years. For a while, the enterprise seemed to be at risk — Stanford withdrew its funding — but staff members from Tanzania continued the research in Goodall’s absence; only one day of data collection was missed.

After two and a half decades of living out her childhood dream, Goodall made an abrupt career shift, from scientist to conservationist. In 1986, she attended a conference of primatologists in Chicago and noticed a common theme running through the papers being presented. “Every single place where people were working, forests were disappearing,” she told me. “It was an absolute shock.”

Then in the early 1990s, Goodall flew in a small plane directly over Gombe. It offered a new perspective on her tiny sliver of virgin forest, which was now surrounded on three sides by 52 rapidly expanding villages full of desperately poor people. In her comings and goings along the lake over the years, she noted some deforestation along the park’s borders, but that had not prepared her for the mile after mile of bare hills she could see from above. Gombe’s chimps needed to cross into suitable habitat outside the park to connect with other chimpanzee populations and maintain genetic diversity, but there would be no such habitat if poverty continued to force a growing human population to chop down trees for farmland and firewood. The flight convinced her that the chimps’ lot could not improve until that of the people living near them did. Goodall now spends about 300 days a year on the road advocating for forest conservation and sustainable development. “It never ceases to amaze me that there’s this person who travels around and does all these things,” she told me one day in Burundi. “And it’s me. It doesn’t seem like me at all.”

Emmanuel Mtiti, a local who directs the Jane Goodall Institute’s conservation efforts around Gombe, was a nurse before he joined the institute, and a skeptic of the outsiders’ intentions. “These guys are tricky,” he told me was the general sentiment. Locals feared that restoring the forests would lead to an expansion of the park and they would lose their land. “But we’ve been able to demonstrate that we are there for them — through health and education, microcredit and other programs of ours,” Mtiti claims. “Now they are happy to see Dr. Goodall in their community.”

It’s not always clear which is her priority today, chimps or humans. Though she sees the work on behalf of each as mutually reinforcing, on balance, the results seem to favor people. Community leaders, elected officials and citizens in several of the surrounding villages told me that work done by the Jane Goodall Institute in the area has probably raised incomes locally and provided health care and education. Whether chimps will also benefit is unknown. Craig Packer, a professor at the University of Minnesota who studies wildlife conservation processes and conducted research at Gombe in the early 1970s, has some doubts that conservation efforts will help the Gombe chimpanzees much in the long run. “I’ve seen a lot of development and aid projects in Tanzania, and they’re awfully difficult to implement,” he says. “Planting a few trees around Gombe is nice. It’s better than not planting a few trees around Gombe. But if you’re thinking of the future of chimpanzees, you’ve got to realize it’s one of dozens of places. It’s a footnote.” Goodall’s institute is trying to preserve habitat in places around Gombe, so that chimpanzees can expand their territory and perhaps counter the steep population decline they have suffered in recent decades. But the work is going to be forbiddingly expensive, and it requires the participation of numerous stakeholders, many of whom wield effective veto power if they choose not to cooperate. Success seems a way off yet.

Goodall encountered some baboons on a walk near Lake Tanganyika. Credit Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum, for The New York Times

Goodall feels the opportunity closing. She says she hasn’t slept in the same bed for three consecutive weeks in more than 20 years. She has lobbied the U.S. Senate and State Department, negotiated with the World Bank and pressured trade groups and chief executives. She told me that she had recently persuaded a group of timber-company executives to adopt a code of conduct that would protect wildlife. Her work on behalf of having wild chimpanzees declared endangered eventually led the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to recommend that captive chimpanzees receive the same status. And after finding herself seated beside the director of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Francis S. Collins, at a dinner one night, she explained to him why she thought the N.I.H. should stop conducting medical trials on chimpanzees. (This has been a cause of hers at least since she wrote about it in this magazine in 1987.) Goodall didn’t get a ban, but Collins looked into the issue and, after consulting other institutions, determined there was little to be gained on behalf of human health by keeping 360 or so chimps in captivity. He announced in 2013 that the N.I.H. would reduce its population of captive chimps to 50. (The agency has retired 66 chimpanzees so far.)

Coaxing the head of a federal agency over a fancy dinner to change policy would, you might think, require a rather different set of character traits than sitting quietly alone in the jungle, observing and categorizing primate behaviors. Field biology, says Robert Sapolsky, a Stanford primatologist and the author of “A Primate’s Memoir,” “requires a huge amount of patience — and this will sound very unromantic — but a capacity for repetition and boredom.” He spent years living among baboons, inspired in part, he told me, by Goodall when he was growing up in Brooklyn. “There’s very little that goes into years of watching monkeys or apes that predicts someone would want to devote themselves to working the crowd of movers and shakers and policy makers. It’s a very rare primatologist who this would be their idea of fun.”

But if her interactions with government officials from the United States, France, Tanzania and Burundi, as well as executives from Silicon Valley, are any indication, the skill sets are not so different: patience, purpose, perception. It took her only a few months of observing chimps before Goodall noticed that some of their behaviors were remarkably similar to those of humans. Now, perhaps, it has come full circle: Her understanding of people has been informed by her time spent with chimps, giving her an intuitive power of persuasion that even she does not seem to consciously grasp.

A couple of hundred yards down the beach from Gombe’s ranger station and lodge, Goodall keeps a small house for herself. This is where she and van Lawick lived with Grub, and the home she later shared with her second husband, Derek Bryceson, a native Briton who served in Tanzania’s first democratically elected government. The house has an actual door, but the windows are chicken wire, to keep animals out while allowing in as much of Gombe’s atmosphere as possible. Lying around are old copies of Science and other journals containing Goodall’s articles — she still shares bylines in major journals, though hers is more a stamp of approval these days than indicative of her own direct research. Somewhat unsettlingly, the house is also full of skulls and other bones from baboons and chimpanzees. We were talking here one afternoon, as waves crashed on the beach just outside, about her activism and how it contrasts with her previous life as a researcher. “I think a lot of what I do with people is the way I talk to them,” she said. “Chimps, you’re not even trying to change them.”

But she was trying to appear nonthreatening with people, I suggested.

“Yes,” she acknowledged. “I’m not aggressive.” Even if she only has a few minutes in the hallway with a senator, she explained, she seeks to be personal, finding a shared concern, asking about the health of a relative. “You try and find something. You would never just walk in and start talking.”

But surely Sapolsky is right about the fact that Goodall found her life among chimpanzees more satisfying than her work as a conservationist. “The best days of my life were spent in Gombe’s forests,” she said at one point to a group of Tanzanian government officials meeting at the Jane Goodall Institute in Kigoma to discuss land-use policies. “People sometimes ask me, ‘Why aren’t you still there?’ ”

The institute is in a single-story, red-roofed, U-shaped building set among several nearby NGO offices — the U.N.H.C.R., for example, which serves refugees from Burundi’s civil war. The local conservation program Goodall created after her flight over Gombe is headquartered here, and the place has become a bit of a hangout for ambitious young locals looking for work or for opportunities to practice their English.

On the road from Bujumbura to the border of Tanzania.

Credit Michael Christopher Brown/Magnum, for The New York Times

Robert O’Malley, a postdoc researcher working at Gombe who happened to be in town, dropped by to show Goodall some pictures he’d taken of the G family of chimps. Goodall first met the original G, Goblin, when he was only a few hours old. He became an alpha male, and when he was finally beaten into submission in 1989, Goodall took him bananas after he was administered medicine to help him recover from his injuries. At least nine of his descendants thrive at Gombe today.

Goodall laughed at O’Malley’s video, which showed a young female in estrus shaking a tree branch in a vain attempt to gain the attention of a nearby male. “That’s hilarious!” she said. “Why doesn’t she just do what they always do and stick her bottom in his face?”

“I don’t know,” O’Malley said.

“They’re an amazing family,” she said. “As vibrant as we’ve ever had.”

“Very strong,” O’Malley agreed.

“Which is the tougher of the twins?” Goodall asked.

“Golden, and her daughter is the same. I love watching the Gs because they’re such a family, and they so clearly enjoy each other’s company.”

“They don’t have to worry about much, do they?” Goodall said, her eyes still glued to the video.

‘It never ceases to amaze me that there’s this person who travels around and does all these things. And it’s me. It doesn’t seem like me at all.’

Few of Goodall’s hours are so reposed. On the day we traveled from Bujumbura, Burundi’s capital, to Gombe, there was some early-morning emailing; meetings with local officials and the ambassadors of France and the United States; a random encounter with a family of Americans in town to train some locals in hotel management; and a four-hour drive in an un-air-conditioned Land Cruiser with stops along the way to visit local chapters of Roots & Shoots. As we drove out of the city, the traffic and crowded shacks gave way to palm-oil trees and cassava fields and then villages, their small structures built of bricks made from the same orange soil. It was hot, and we’d just had lunch; I expected Goodall, who flew from London two days before, to take a nap. Instead, she pulled out a legal pad and pen and began jotting down ideas for how to cheaply procure a vehicle for Burundi’s Roots & Shoots. A few hours later, a detour necessitated by a broken bridge had turned us into the setting sun. “Oh!” Goodall said, bringing her hand to her chest. “Look at that!”

Continue reading the main storyContinue reading the main storyContinue reading the main story

By the time we reached the border with Tanzania, darkness had fallen. Technically, it was too late to cross. We knew others who’d arrived so late and been sent back. Collins got out of the truck to speak with the uniformed Burundian manning the post while Goodall and I stayed in the car, swatting mosquitoes. “I’m so glad to leave it to other people to negotiate,” she said. “So often it has to be me.”

The border guard said he would permit us to cross if his Tanzanian counterpart would, so we drove 100 yards down the beach to Tanzania’s border post, and the official there agreed. After taking our names and passport numbers, he wanted to match faces to passport photos; shining the light of his cellphone onto Goodall’s face, he remarked, “You look tired.”

“You’d be tired, too,” she responded cheerily. “I’ve given lots of speeches today, to ministers and ambassadors.”

Collins asked if she wanted to sit down while the border official finished his paperwork.

“No, I don’t want to sit down!” she said. “I’ve been sitting — I want to dance around the room!” And Goodall proceeded to shuffle across the bare cement floor, hands in pockets, seemingly energized despite the conspicuous absence of music.

Half an hour later we were speeding across the waves under an enormous, orange waning gibbous moon rising over the mountains. Goodall knew we had reached the park when she noticed a change in the scent of the air, from the denseness of the vegetation in its protected forests.

Goodall had been working for 13 hours — a long day, but it produced news of one notable success. On her most recent visit to Burundi, in 2013, she discussed with the French ambassador, Gerrit van Rossum, the situation with Burundi’s Vyanda Park: Refugees from the country’s decade-long civil war were returning home and building houses in the park and along its edge. She told van Rossum she didn’t think the government could devote the resources to enforce the park’s legal protection. Today, at one meeting, van Rossum told Goodall that after that visit, he persuaded France’s government to come up with the cash to hire park rangers. They would also finance outreach, hoping to persuade residents that conserving the forest would promote tourism and with it, development.

“Can you imagine what it’s like for me to hear, ‘Because of your last visit, we’re doing this work’?” Goodall said. “You never know who it’s going to be, or what they’re going to do. But as long as I do it, it keeps happening. So you can see why I can’t very well stop.”